Madness, Rack, and Honey

Have you noticed that when you follow the career of an artist or thinker who’s interested in constant self-development, the advancement of the particularities of their art or craft or science more than the commercial viability of their increasingly refined and complicated projects, you watch them leave the earth’s atmosphere for some rarefied stratum that’s too inaccessible (requiring spacesuits and jet fuel for escape velocity, etc.) for most people to follow? The music gets weird and undanceable, the films more and more indie, and the nutritional smoothies recipes start leaving out all fruit whatsoever and adding some obscure bitter powders to become undrinkable sludge, and you think, “What happened here?!”

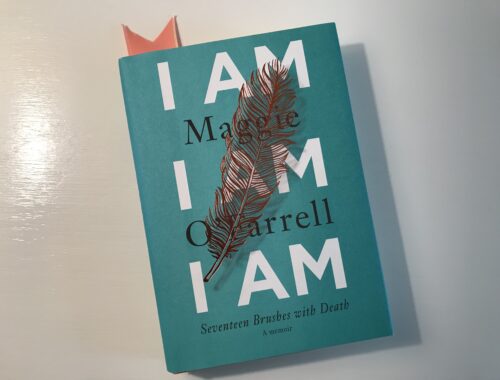

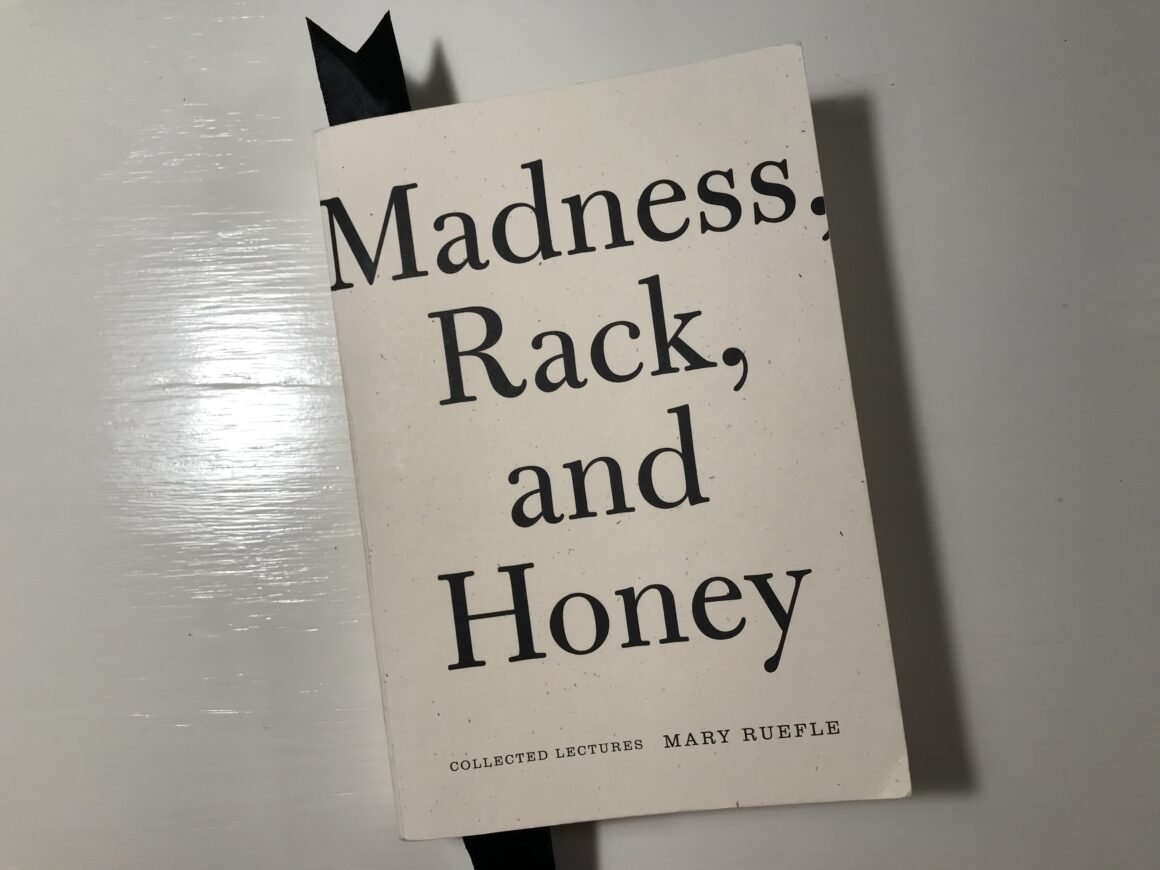

I found the poet Mary Ruefle not long ago, through this collection of her lectures published in 2012, which I love. I love the crisp cottony materiality of the book itself, as well as the lectures and their arrangement, which are hilarious, heartbreaking, incisive, slyly looping and reconnecting, over long stretches of pages and passages. I’ve laughed out loud until I was gasping as I made my way through her self-deprecating accounts; I’ve forced my family to listen to long read-alouds as she tightly constructs a perfect, complicated point; I’ve dogeared and marginalia-ed, despite how flawless even the paperback printing is. I’ve gone back to the beginning to witness the construction of it, now that I know how it ends, how all the pieces fit together. I’ve loved her even more for referencing among the lectures and in her wide-ranging bibliography at the end many of my own favorites, including Carl Jung and John Berger and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, which is uniquely and supremely delicious to me, its own flavor of honey, and chocolate. But when I further explored her oeuvre by focusing on her most recent poetry collected in Dunce and published in 2019 (I have yet to access her visual art form of erasures), I found myself lost, wandering among the words, searching for meaning and resonance. There could be a great joke here (as in, I myself am the titular dunce), but I find myself wondering at the possibility that a poet may be more brilliant as a lecturer (who writes the lectures out completely, then reads from her writing, but she wrote each lecture with the intention for it to be read it aloud—which most poetry also is) who writes/talks about poetry, about herself and others as poets, about the subjects of poetry—life itself, all its specificities and messiness—than she is as an actual poet. Or maybe it’s that when it comes to her poetry, published seven years after lectures, there’s not quite the oxygen for me. So—I’ll blend a berry smoothie, listen to Sting sing “Fields of Gold,” and reread Ruefle’s first of her twenty-two short lectures (247): “WHY ALL OUR LITERARY PURSUITS ARE USELESS: Eighty-five percent of all existing species are beetles and various forms of insects. English is spoken by only 5 percent of the world’s population.” And her second one, on the next page: “WHY THERE MAY BE HOPE: One of the greatest stories ever written is the story of a man who wakes to find himself transformed into a giant beetle.”