DEAR Day

The children’s book author and former school librarian Beverly Cleary passed away last month, on March 25, at the age of 104. Her birthday, April 12, is also National Drop Everything and Read (DEAR) Day, established years ago both to honor Beverly Cleary and to encourage families to read together regularly; elementary schools often have a DEAR time in their schedules. As someone who will take any opportunity to drop everything and read (either solo or with others), and who has spent thousands of hours reading with my family, I deeply appreciate the celebration—of the lifesaving and life-expanding work of all librarians and reading teachers everywhere, of Cleary herself and her vast artistic productivity, and of Cleary’s characters, who have lived their perfectly imperfect young lives with energy and forgiveness since 1950. Did you know that one of Cleary’s earliest memories was of tripping and skinning her knee, of putting a hole in her stockings with the stumble? Her mother told her never to forget that day, which Cleary didn’t. But her mother wasn’t shaming her about the ruined tights; that day was Armistice Day, the end of World War I. Cleary remembered the end of the First World War: Her witness to it is part of what it can mean to live more than a century.

We were on one of our stretches of road trips with our three boys, driving down I-5 from Olympia, Washington, to Sacramento, California, I think, winding our way through the mountains in Oregon. In the front passenger seat, I was reading aloud Henry Huggins, Cleary’s debut novel, her first introduction to readers of what would become a whole vibrant community of characters. I often halted in my reading because of laughing out loud at the scenes Cleary constructs. Many things in life amuse and delight me (dogs among them—Ribsy!), but I’m not easily drawn into full-bodied laughter, face and lungs and belly engaged; part of why I love Beverly Cleary is that her writing does that to me. What was the passage that shut me down completely that day, where I had difficulty getting enough breath for how hard I was laughing? Where I couldn’t make out further words for the hot tears pouring from my eyes? Where just the thought again of the previous sentences triggered giggles? If it’s been a while since you’ve read Henry Huggins, maybe revisit him and his world, if you’re in the mood for that kind of sweet catharsis.

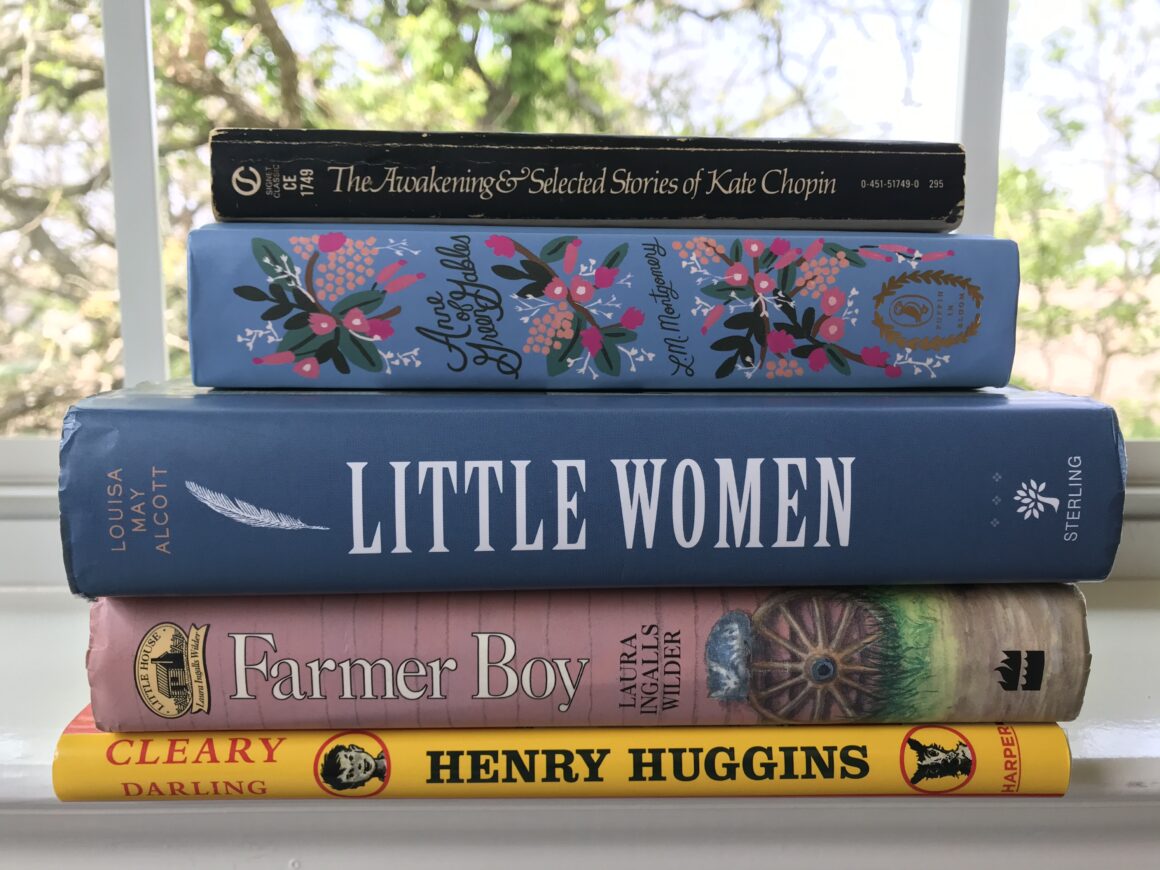

Henry—including Ribsy, of course!—were my favorites among Cleary’s characters when I was a child, along with Ralph, the motorcycle mouse. Farmer Boy was my favorite in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series; Jo’s Boys my favorite in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women series. As a woman friend from college pointed out to me one day, years after our graduation: “You have always liked boys.” Yes, but it was more than that, and here’s my confession: The beloved female protagonists of these classic childhood stories were girls I recognized, admired, and loved—on the page and in their doppelgängers around me—but I didn’t identify with them as myself. I could see that the truth was that I was another character in the story: I was the Beezus, not the Ramona; the Mary, not the Laura; the Meg, not the Jo; more Diana than Anne with an E. In later readings, I was probably more like the “mother woman” Madame Ratignolle than Edna Pontellier, with her “inward life that questions” in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening. So at the same time that the protagonists in the stories were envying the seemingly easy grace and societal approval of their older sisters or best friends, I was envying those girls’ spirited outbursts and unapologetic expressions of authentic self. And Beverly Cleary made that leap in middle age, from dutiful librarian to prolific writer. My hero.