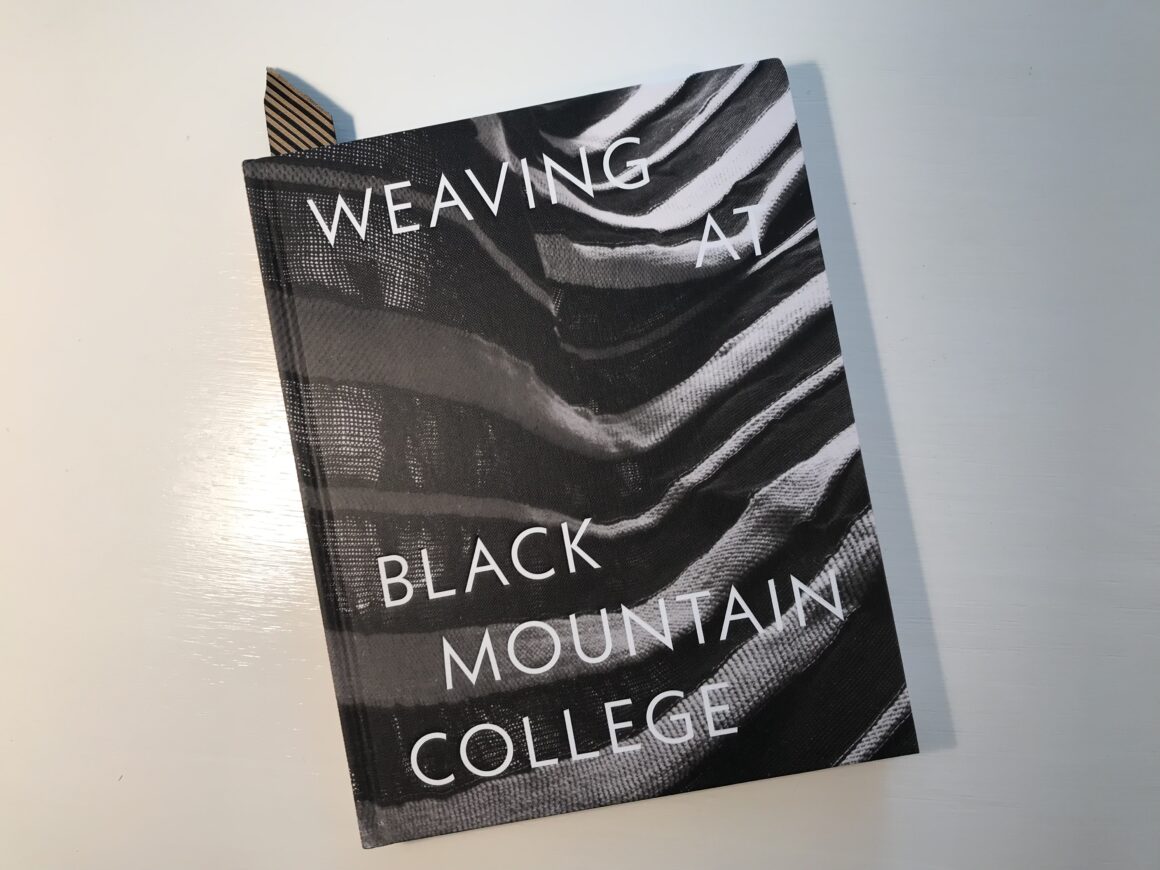

Weaving at Black Mountain College

When R. and I stopped recently in Asheville, North Carolina, on our way back to Austin along our 5,431-mile road trip in support of one of our sons settling into his new home, I took a few hours to visit and study the exhibit “Weaving at Black Mountain College: Anni Albers, Trude Guermonprez, and Their Students,” currently on view through January 6, 2024, at the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center. The exhibition’s illustrated catalogue is a faithful and comprehensive study of the exhibit itself, as well as the immediate and wider contexts of the textile pieces, academic ephemera, and commercial remnants on display. Despite accurate reproductions in the full-color catalogue of the weavings, it is impossible to convey fully on the printed, bound pages the richness and visceral engagement of being within touching distance of the woven materials.

There were ample photographs at the exhibit—and within the catalogue—of the students/artists at work both in their years at Black Mountain College and, in some instances, in the careers they made in the decades after. (They are surprisingly contemporary-looking in their artists’ work clothes and with their loose hair, but consistently quite thin, their ropy muscles close to bone within the Depression and WWII). What I kept seeing, though, was the evidence of their hands on the threads, the ghostly hovering and traces of their fingers and palms, the mapped flicks of their now-laid-to-rest wrists, making manifest their design visions in their small sketches, samples, and studies, in their final school projects and more sophisticated career products. All of that materiality, all of the archival record available for BMCM+AC’s new curation, was saved and stored and preserved, by the artists themselves, by their families and friends, by—in some cases—institutional entities, weight from the artists’ present carried into their future marking the past for us now.

A few of the pieces in the legacy section of the exhibit—the tracing of artistic influence and genealogy from Black Mountain out into the rest of the world—had a powerful effect on me, especially two pieces depicting butterflies: Trude Guermonprez’s (1910 – 1976) linen, wool, and silk “Hummingbird Cages,” c. 1963, and especially Porfirio Gutiérrez’s (b. 1978) wool dyed with cochineal insects “Untitled,” from his “Transmigration” series, 2022. (See https://www.porfiriogutierrez.com/nature) I was deeply interested in the aesthetics of the pieces—Guermonprez’s airy construct and Gutiérrez’s almost felt-like density of ombré magenta—and in the artists’ impulses and developmental arcs, but it was the multiple strands of connection between their work and the efforts and artifacts of my own family of origin, my created family, and my current doctoral program and cohort that most awed and inspired me, and I came away with my head, hands, and heart itching to make.