“Nothing is easy when you might come apart in the middle at any moment.”

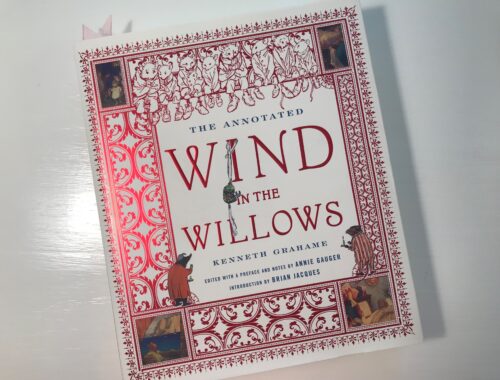

So, I have a mild synesthesia, where when I read aloud, my mouth fills with tastes and textures prompted by the writing. It’s not that the words convey for me the specific flavor of, say, Glazed Five-Spice Chicken (unless I’m reading Samin Nosrat’s peerless adaptation of David Tanis’ recipe of the same), but that some (bad) writing tastes like eating sand, or gives my mouth the effect of being extremely thirsty, or prompts a gag reflex. It’s not the subject matter, necessarily, unless the writer seems to be lying or is completely unimaginative—or the (usually children’s) book is a shameless commercial ploy to expand the reach of a kid’s movie through a terrible, cheap, and poorly illustrated companion paperback. I try to avoid all these sorts of experiences, of course, and seek out texts that are delicious: meaty or silky or crunchy or effervescent, a delight on the tongue, a feast of substance, or perhaps just dessert. Kenneth Graham’s unabridged The Wind in the Willows heads the list of delicious books I’ve read/eaten; its pleasures of both form and content are so reliable that I usually read the story aloud to R. every spring, the ideal way to switch from the heavy meals of winter to all the bright flavors that spring and summer offer.

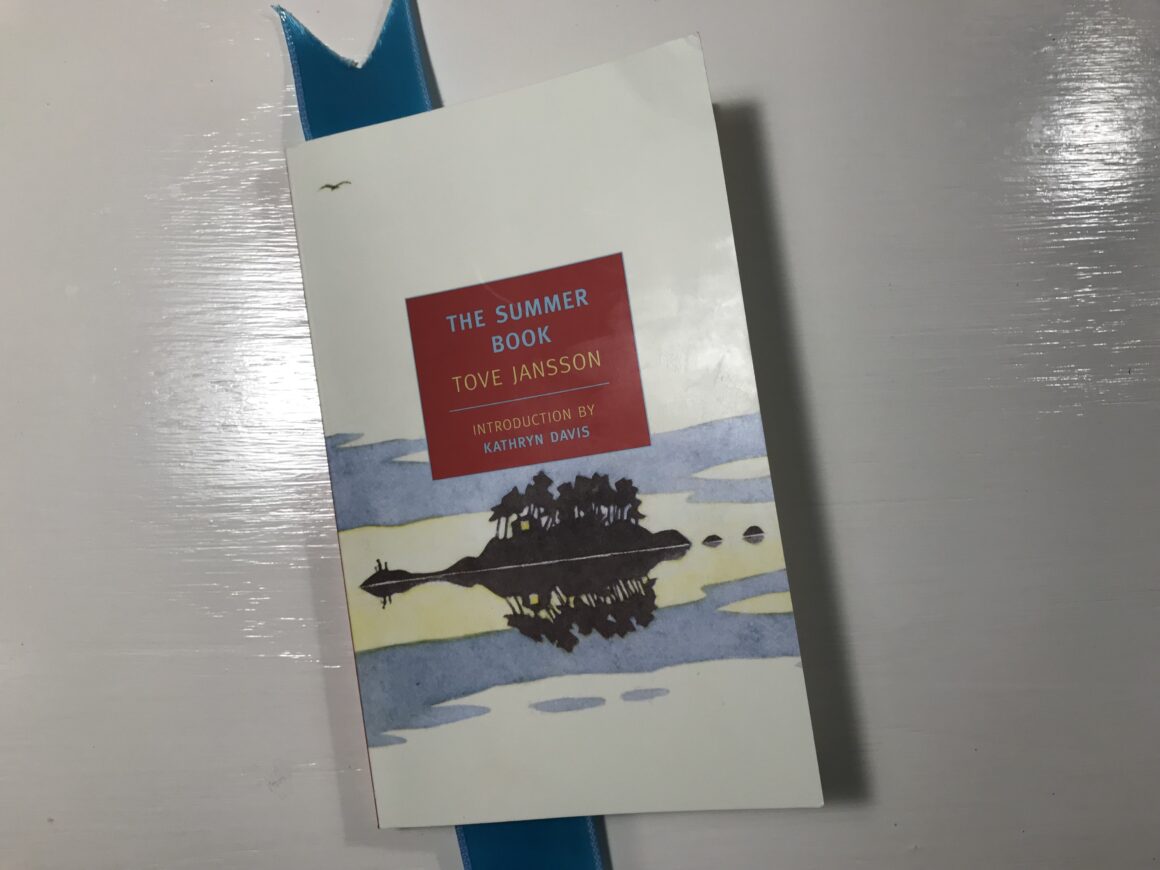

Although we’re nearly at the autumnal equinox, I just discovered this past week The Summer Book, by Tove Jansson (1914-2001), and I’m reading it aloud to R., both of us devouring its lyrical, lucid perfection, wanting “just one more” of each of its short chapters. It’s a story set on an island in the Gulf of Finland over a summer at an unspecified time (although probably in the early- to mid-20th Century), and there is really no plot, just the precisely observed details—the perfect tapas, to mix cultures—of the daily explorations and considerations of Grandmother and quintessentially six-year-old Sophia. My mouth is watering just thinking again about our reading session last night, which included laughing to the point of tears over a wild and wise conversation between the two—both of them cantankerous, a combination of personality and developmental stages—about God and religion. With Jansson’s handling, the pair’s courageous expressions of their contemplations about the biggest issues of life and death themselves—even with Sophia’s having recently lost her mother—still manage to be more homemade chocolate custard with stiff whipped cream than lean beef. Love and grace: the best items on anyone’s menu.